Wise Guy: Lessons from a Life

March 06, 2019

Guy Kawasaki's new book "covers everything from moral values to business skills to parenting." In this excerpt, he discusses why the toughest teachers are the best teachers.

Guy Kawasaki has been a fixture of the tech world since joining Apple's Macintosh team in the 1980s. He is currently the chief evangelist of Canva, the Australian “unicorn,” and a brand ambassador for Mercedes-Benz.

Guy Kawasaki has been a fixture of the tech world since joining Apple's Macintosh team in the 1980s. He is currently the chief evangelist of Canva, the Australian “unicorn,” and a brand ambassador for Mercedes-Benz.

His bestselling books, including The Art of the Start 2.0, The Art of Social Media, and Enchantment, have established him as an expert in innovation, entrepreneurship, venture capital, and marketing. But his new book is a radical departure from the other fourteen that he’s written. Wise Guy: Lessons from a Life is his most personal book yet. Told in a series of vignettes, it details Guy’s wide range of experiences and the lessons he’s learned from them. The book covers everything from moral values to business skills to parenting. As Guy writes, “I hope my stories help you live a more joyous, productive, and meaningful life. If Wise Guy succeeds at this, then that’s the best story of all.” Guy writes on a wide range of experiences and reflects on the lessons he’s applied to his business philosophy and life. For instance:

- Pay it forward: Guy’s uncompensated support for brands helped him build the relationships that led to his success with companies like Mercedes-Benz.

- Kindness to strangers goes a long way: You never know who you might meet in, say, an Apple store on University Ave in Palo Alto (hint: it’s Guy).

- Add value to people’s lives: Think like NPR – they create high-value content which results in the successful solicitation of donations and gifts.

- The best leaders are humble: Richard Branson once polished Guy’s shoes to encourage him to fly Virgin Airlines. “I never saw Steve Jobs get on his knees to get a customer,” Guy notes in the book.

- You’re never too old to learn something new: Guy took up surfing at age 62. The acquisition of skill is a process, not an event, and the process itself can be the reward.

Chapter Two, "Education," begins with a quote from C.S. Lewis: "The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts." In the excerpt below, we meet his high school AP English teacher, get a few lessons in good writing, and learn why…

The Toughest Teachers Are the Best

Before you read this section, think about the best teachers you had in your life—at any time, in any subject. Go to that place in your mind, and you’ll get the full impact of what I’m about to tell you.

At the age of fourteen, I entered the seventh grade at ‘Iolani. This was a private Episcopalian college-prep school that provided instruction from kindergarten through the twelfth grade. When I attended, it was an all-boys school with a graduating class of 150 students.

Looking back, ‘Iolani was a great experience. There were many teachers (Charles Proctor, Joseph Yelas, John Kay, Dan Feldhaus, and Lucille Bratcher), coaches (Ed- ward Hamada, Charles Kaaihue, and Bob Barry), and staff members (William Lee and David Coon) who taught me how to think, how to work hard, and how to be part of a team.

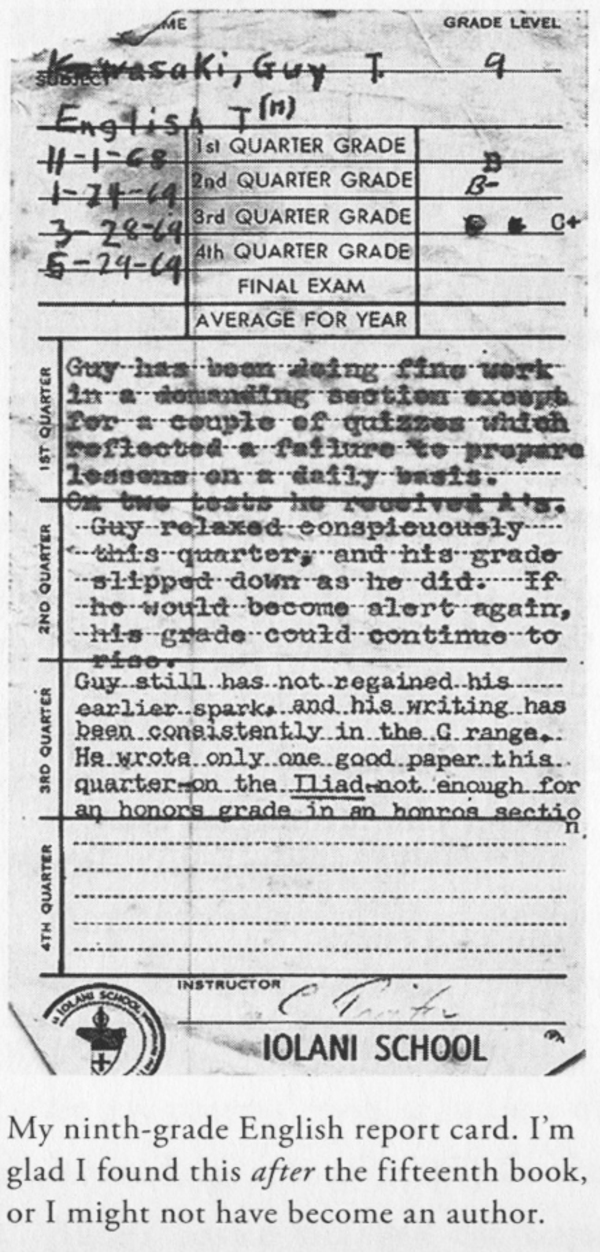

Although I thought I did well in high school, I found my ninth-grade English report card when doing research for this book. It’s pictured here; talk about selective memory! Somehow, luckily, I got through Honors English and into Advanced Placement English and became a student of Harold Keables.

Although I thought I did well in high school, I found my ninth-grade English report card when doing research for this book. It’s pictured here; talk about selective memory! Somehow, luckily, I got through Honors English and into Advanced Placement English and became a student of Harold Keables.

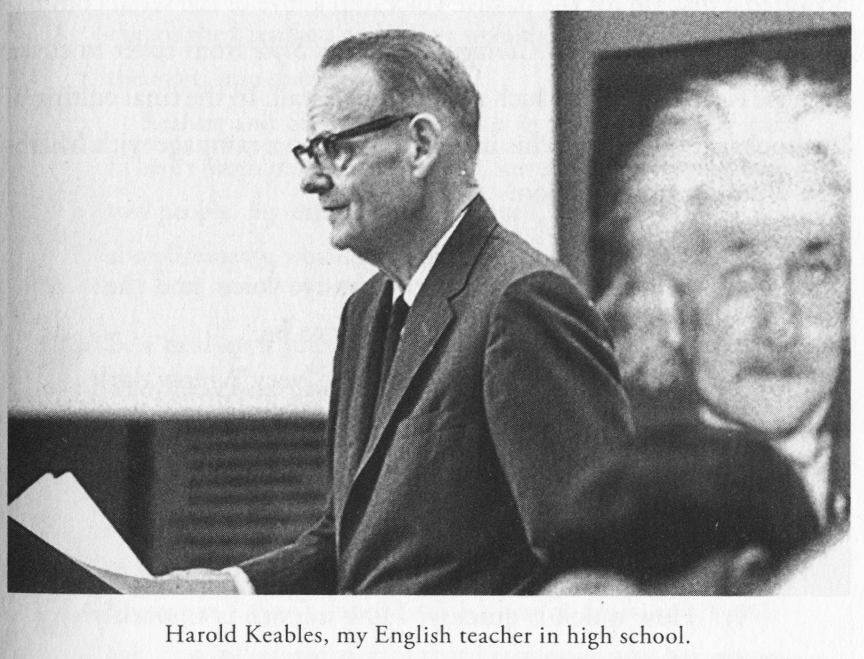

Of the ‘Iolani faculty and staff, Keables had the greatest impact on me. He was my AP English teacher—and the toughest teacher I had at any level of education. He was the most demanding, and he taught me the most. (There’s a causal relationship there.)

I hope you have a Harold Keables at least once in your life. He taught me to hold myself to high standards and the value of hard work. For example, here’s how he taught writing:

- He circled the errors that you made in your essay.

- You copied the sentence as you originally wrote it.

- You cited and quoted the rule that you violated from Good Writing: An Informal Manual of Style by Alan Vrooman.

- You rewrote the sentence correctly.

- You turned this in as homework and hoped you got it right the second time.

This was the 1970s—long before personal computers and word processing, so we wrote everything out in cursive, using a pen. When every error involved a three-step process to correct, you learned the rules of grammar and spelling after only a few papers. Keables is the reason I acquired a disdain for the passive voice and a love of the serial comma. Eventually I read The Chicago Manual of Style from cover to cover, because Keables inspired such attention to detail. In the final editing of my books, also thanks to his influence, I go on a rampage with Microsoft Word’s search function:

- “Be” is a smoking gun for the passive voice, and the passive voice is weak. To be is not to be.

- “Very” is imprecise—how much is “very”? How dark is very dark? How fast is very fast? How scary is very scary? How good is a writer who is dependent on “very”? Not very.

- Adverbs are for wimps, so I purge words that end in “ly.” How quick is quickly? How smooth is smoothly? How rich is richly?

- “Kind of” is not an approximation. It is a type of or an example of—for example, a hibiscus is a kind of flower, but it’s not “kind of” (moderately) pretty.

You were the Man, Harold Keables!

Wisdom

Seek out and embrace people who challenge you. You will learn more from them than from the folks who hold you to lower standards. When you look back years later, you will realize that the toughest teachers and bosses were the ones who taught you the most. Iron sharpens iron.

Keables and Steve Jobs are both in this category for me. (There’s much more to come about Steve.) Were it not for these two people, my expectations of myself, and therefore my accomplishments, would have been lower.

Be a hard-ass if you are a teacher, manager, coach, or someone who influences people. You’re not doing anyone a favor by lowering your standards and expectations in an effort to be kind, gentle, or popular. The future cost of short-term kindness is great.

Be patient. I wasn’t one of Keables’s best students, so he’s probably now in heaven, amazed that I’m the one who has written fifteen books. If you’re a teacher, you never know which student is going to internalize what you taught and run with it. It may take a while—you can’t measure the impact of a teacher until at least twenty years have passed—but it can happen.

Thank the people who helped you achieve results before they are gone, as I advised regarding Trudy Akau. You’ll regret not doing so if the opportunity passes.

Excerpted from Wise Guy: Lessons from a Life by Guy Kawasaki

Published by Portfolio/Penguin, and imprint of Penguin random House LLC

Copyright 2019 by Guy Kawasaki

All rights reserved

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Guy Kawasaki is the chief evangelist Canva, an online graphic-design tool. He’s also a brand ambassador for Mercedes-Benz and an executive fellow of the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley. He was previously the chief evangelist of Apple and a trustee of the Wikimedia Foundation. His previous books include The Art of the Start, Enchantment, Selling the Dream, and The Art of Social Media. He has a BA from Stanford and an MBA from UCLA, as well as an honorary doctorate from Babson College. He and his wife, Beth, have four children.