Slam-dunking New Boxes In a New Century

February 24, 2009

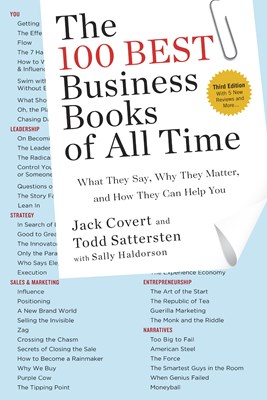

In 1994, Dave Dorsey wrote a great book call The Force about the Xerox salesforce that he followed around for a year. The book is so good we included it in The 100 Best. He has written a short piece for us about what the parallels exists between what he wrote about in The Force and what he see going on today: The current financial crisis brings back memories for me.

In 1994, Dave Dorsey wrote a great book call The Force about the Xerox salesforce that he followed around for a year. The book is so good we included it in The 100 Best. He has written a short piece for us about what the parallels exists between what he wrote about in The Force and what he see going on today:

The current financial crisis brings back memories for me. It reminds me of what I saw in the early 90s when I spent a year inside Xerox Corporation doing research for The Force, the story of a top sales team's effort to make its annual goal. Many years earlier, Xerox had been hailed by some as the greatest success story in American business. In the 60s, it made its shareholders astonishingly rich, after having invented and successfully convinced nearly everyone to buy the office copier. In thirty years, much had changed for Xerox. Its patents expired, and Japan started eroding its market, luring customers away with less expensive equipment. Also, technology had advanced. Xerox knew it had to get out of the copier business and move into digital networked printing systems. One way to approach this challenge might be to lower earnings projections for a transition to a new and better business model. But you don't tell Wall Street you're taking a sabbatical from profitability in order to retool. So, the company struggled to become something new, where reps would sell results and solutions through new processes, rather than pushing the latest model of copier. Yet to keep up its earnings, that's just what it had to do: keep "slam-dunking" new "boxes," as it called them, onto the premises of buyers who didn't always need them.

Xerox was having a harder time finding new customers, so reps were going back to their existing customers to lease a new machine before the old machine's lease was up. That meant having to say, "we'll make the balance on the old lease go away" while "baking" that remaining debt into the sum that would then be paid out, in installments, over the life of the new lease. Customers didn't realize they were still paying off the old lease in their premiums for the new lease. They also didn't realize, or didn't care, that their debt was getting larger and larger with each new lease, partly because the new contracts were also getting longer--from three years to four to five--in order to keep the monthly payment at a level that wouldn't shock anyone in accounts payable. Revenue from these premature leases would go into the Xerox quarterly and annual reports, so on the surface, everything looked fine. Yet it was all a way of forcing success to happen. And it was unsustainable. Ultimately, in desperation, the company began booking its service and lease revenue--for the life of the entire lease over four or five years--in the first year of the lease. That kind of accounting cost top Xerox executives tens of millions of dollars in fines later in the 90s when the SEC cracked down on the company.

Why do these memories keep coming back now? Because, the year I was inside the company walls, watching and listening, Xerox was giving me a glimpse, in microcosm, of what was going to happen to the economy at large. Over the past quarter century our manufacturing has been decimated by foreign competition--first by Japan, in the case of Xerox and others, and now by China and India, throughout domesting manufacturing. As we've lost our manufacturing base, we've become a FIRE economy, relying on finance, insurance and real estate to prop it all up--industries that appear to thrive on accounting principles when times are good and accounting games when times are bad. (Xerox itself moved disastrously into finance for many years, buying up other finance companies, emboldened by its own success in working the numbers.)

The nation as a whole has followed in this company's footsteps. We were once a manufacturing superpower. But our markets have shrunken dramatically, because, as Xerox did, we've taken assumed the future will resemble the past. We can't make things as economically as countries where labor costs so much less. We've become too rich for our own good, and we don't want to give up the quality of life we've grown accustomed to. As a result, through the illusory dot.com bubble during the Clinton years and then the real estate bubble during the Bush years, we've refused to heed the truth about our loss of manufacturing. For me, the current crisis follows a familiar pattern of decline: the false appearance that everything is on the uptick, while in reality it's all eroding, ending in a day of reckoning. Though Xerox isn't the fabled beacon of American ingenuity it once was, it seems to have put its house in order under its current CEO. It has largely become what it wanted to become: a digital printing company that offers services to help customers better manage documents, both electronically and on paper. Maybe that's cause for hope.

I liked the people I got to know at Xerox. They wanted want most people want: a good home, a nice car, and money for college. Most of them hated having to play games with the numbers to have those things. They must have felt relieved when they were required to clean up the way they sold products and do only what it was in their power to do, given the rules of a new, global economy. It's a challenge we all face now, to reset our expectations at a realistic level and quit playing financial games, with rising levels of debt. Maybe it means a smaller house and a new car every eight years instead of every three. Maybe it means the state university rather than the private school--or a trade school rather than a college. Possibly, it requires even greater sacrifices that no one wants to talk about. When it's over, who knows, it might come as a relief for all the rest of us, as well, when we start living within our means, as Xerox appears to be doing now.