The Absence of Presence: The Position of Women Authors in the Business Genre

February 24, 2016

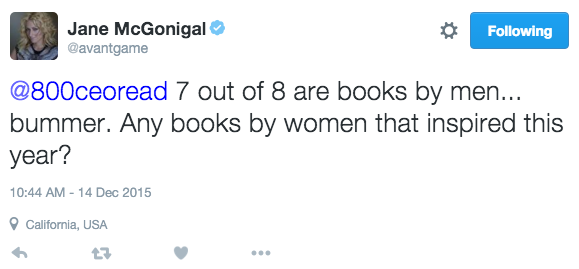

A pointed question from Jane McGonigal led our General Manager, Sally Haldorson, to take a closer look at the underlying bias against women authors in the business genre.

Two months ago, Jane McGonigal, game designer and author of SuperBetter and Reality is Broken, whose work on gaming blended with social and neuroscience embodies the multi-layered and provocative ideas we as a company fall head over heels in love with, tweeted that she was disappointed to see that only one of the eight books we selected for the 2015 Business Books of the Year shortlist was written by a woman author. If I were a gamer, perhaps I'd be able to stitch together an apt metaphor for the impact of her comment, but needless to say, she hit her target.

First, I reacted defensively, albeit accurately. We did have a strong percentage of women authors in the longlist (about one-third). And books such as Clay, Water, Brick: Finding Inspiration from Entrepreneurs Who Do the Most with the Least by Jessica Jackley and Anne-Marie Slaughter's timely Unfinished Business were strong contenders in our final conversation to be category winners. The reasons other books prevailed were varied, but put simply, we believed the winners we chose were the best representatives of the category in which they had been submitted.

This concern seemed the most pressing: How much of our awards criteria were limiting the emergence of new voices, particularly women's voices, in business writing?

And yet that first response, once the magnifying glass was employed, didn't seem a satisfactory answer, and revealed itself instead as a part of the problem. Once I lay aside my knee-jerk defensiveness, I began to wonder if we weren’t judging our business book awards a bit like the Westminster Dog Show. I don't mean that as an insult, either to dog shows or to our own awards, but standards of breed aren’t fluid and neither, it seemed, were our business book award categories.

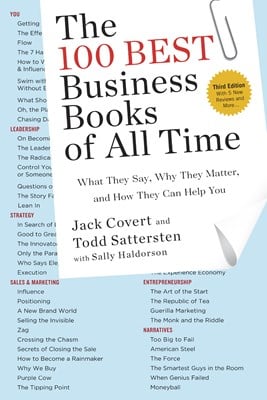

Over the years, we had created categories we reused time and again, categories that stemmed in part from our lists in (the admittedly male-author-heavy) 100 Best Business Books of All Time, but also out of traditional business mores and values. Once we put those categories in place, publishers, authors, and publicists were forced to choose one of them in which to drop their nominees. Those pre-categorized books were then held up to our own kind of “breed standard.” In The 100 Best, we enumerated three judgment criterions: the quality of the idea, the applicability of the idea, and the accessibility of the format and language.

In the case of our awards, however, each juror is not only given the task of deciding which of the year’s books met that general criteria, but also which met the standards of the category they had been given to judge. The best Leadership and Management book, then, would offer a quality idea that was applicable and accessible, but past that, the juror was left to decide if the book met a rather amorphous and subjective standard of what a Leadership and/or Management book should be in the year which it was entered. While there is nothing wrong with expert subjectivity—after all, we are all human—most of our efforts went into assessing the books, not actually critiquing the process of categorization within which that assessment happens.

WHAT’S THE MATTER HERE?

This concern seemed the most pressing: How much were our awards criteria and categories limiting the emergence of new voices and viewpoints, particularly women's, in business writing? We aren’t interested in promoting representation as a criteria, as we believe the quality of the idea and the writing itself are without doubt why any book should be lauded, but, if we expect writing by women to act like the writing done by men—or, to take it a step further, that the thinking being done by women should echo that being done by men—and then that it should be rated or regarded by the same criteria as men's, then we likely have a problem of discernment. This article (which has become an internal discussion in our company since I passed the first draft on to our editorial staff over a month ago) is my attempt at finding out how I, and the editorial staff at 800-CEO-READ, can work in a way that does not give in to tokenism, but celebrates women authors in business literature rather than hide their light under a canonical bushel.

While reinventing our awards categories struck us as a worthy mission, it didn't solve a more concerning issue for myself: Why hadn't I been using whatever platform I have to change the conversation, instead of continuing to contribute to the old conversation? Over the years, I've written some pieces that reflect upon the problem of how business books written by women have been handled within our industry. I've lamented the fact that over much of the past decade, while there were more books by women published, those books were packaged more like "chick lit"—covers featuring high heels, short skirts, and titles with double-entendres bolded in pink print—which distinguished them as being "for women" rather than anything a businessman might read.

While I have been particularly critical of the way in which publishers often treat business books by women authors, it seemed too that the authors themselves were defaulting to messages of empowerment or creating new versions of old tropes, and were not free to write works that were thoroughly non-gendered. Perhaps they were writing to an identified market, set up by publishers, and not competing in heavily male-dominated categories. Perhaps they too were limited by their own internal biases. Perhaps they were simply doing the same work that so many women writers have done before them: giving women a voice.

I'm not intending to invalidate the worth of books by women for women, particularly in an under-represented genre where mentoring is the best way for women to guide other women, but books that were geared specifically toward empowering women, and didn't make an attempt at reaching a general audience, were difficult to advocate for consideration. Yes, many women need tips on how to negotiate a raise, but the limited scope of the book simply didn't offer much purchase to grab onto in a review. And, those books certainly weren't going to help women authors grab a foothold with male readership. (In retrospect, this criticism seems flimsy. Certainly we have chosen books that focus on a specific business problem, so why not assess books written for women by women as viable solutions to that particular problem?)

Certainly there has been a handful of women business authors like Rosabeth Moss Kanter, Margaret Heffernan, and others who are able to publish more generalized material, and female journalists like Bethany McLean and Kathryn Schultz are very popular business and cultural event writers. Jane McGonigal herself, of course, works and writes successfully in a more niche category (gaming) that has been openly hostile to women at times. But these authors still seem like exceptions at the moment.

While reinventing our awards categories seemed a worthy mission, it didn't solve a more concerning personal issue I had: why hadn't I been using whatever platform I have to change the conversation, instead of continuing to contribute to the old conversation?

Of the 370 books submitted to our business book awards this year, nearly 100 were written or co-written by women, approximately 25 percent. And women authors wrote 20 percent of our company’s bestsellers for 2015. Conversely, The 100 Best Business Books of All Time, published in 2008, included only 6.5 percent women authors. (The new edition coming out in 2016 seeks to remedy this.) This indicates some progress in the number of books being written for, and that represent, a more balanced workforce. But there is much more to accomplish, and I want 800-CEO-READ to be out in front.

COGNITIVE DISSONANCE

I didn't know I was a feminist until I went to college. Growing up in a small farming town in southern Minnesota, I was far more concerned with fitting in with the 26 other kids in my class than bucking stereotypes. At the time, I may have been able to regurgitate names like Gloria Steinem and Ms. Magazine, or even Marlo Thomas and one of my favorite childhood albums, Free to Be You and Me, which lauded boys who cried and girls who liked to fish and every kind of person in between, but my knowledge about their actual accomplishments was slim. Still, I knew there was something different about me and my best friend from about 9th grade on. Rather than dating local boys, playing sports, and planning families, we talked about what we would do when we left town. Staying was never an option. We read, and then wrote, stories about modern women who did things. These women we read about modeled a life quite different from the roles our mothers and friends' mothers more typically performed. And so, our imaginations were shaped by those stories that inspired us to pursue lives/livelihoods that would finally take shape in some fictional city with work as artist, professor, or CEO in a power suit. (What? It was the ’80s!)

My friend and I went on to attend the same private college in Minnesota, but then we went our separate ways. I took women's studies courses, volunteered for NARAL and marched for women's rights, studied feminist interpretations of religious texts, wore Doc Martins and smoked skinny cigarettes and read Plath. I refused to read canonical authors as Hemingway and Faulkner and Roth, declaring them sexist at best, misogynistic at worst. (I regret this now, because I think there is value in reading all literature as long as one can stay aware of what bias is present either in text or subtext.)

In graduate school, I moved forward along that same trajectory. In my classes, I fell for the autobiographical writings of women like Charlotte Perkins Gilman, women who had been derided for putting ink to paper and glorifying the mundanity of the domestic. I intimately felt the repression of the wealthy women in Wharton's New York and Woolf's England. I tried hard to learn what I didn't know about the women's lives revealed in such books as Corregidora and Sula. I admired, and thus emulated the skill, style, and substance of Moore, Gilchrist, Didion, Dillard, and Kingsolver. When I defended my Master's thesis, the list I was required to submit as evidence of the breadth of my reading was decidedly female. I believed (and still do) that the personal is the political, and my reading has always reflected my interest in articulating, absorbing, and exploring the particular and peculiar in women's lives.

Most of the time, I favor books that speak to some question I'm trying to answer for myself or within myself. I rarely venture far from my preference for reading women authors at home, because reading is, to me, the opportunity to find common ground with other people in the world. And that connection is easier to find when that person or experience has been crafted or lived by another female. Some might accuse me of being a narrow thinker, but I would hope that if my breadth is narrow, my depth of thinking has many strata.

Essayist Rebecca Solnit, who addresses the subject of gender in writing and reading in her LitHub article “Men Explain Lolita to Me,” suggests that reading can enable us “to go deeper within ourselves, to be more aware of what it means to be heartbroken, or ill, or six, or ninety-six, or completely lost.” That kind of reading experience is most meaningful to me. While I know plenty of other female readers who are most satisfied by exploring worlds and lives least like their own, I thrive when surrounded by a community of women's voices. Is that a bias? Undoubtedly. And I’ve got to own it, just like the majority of publishers, book authors, media channels, and book sellers need to own their inherent biases in the professional realm.

Now, 20 years post-graduate school, and with the majority of those years spent reading and reviewing business books, I have come to believe that the personal is also the professional. Or, if that makes people uncomfortable, maybe that the personal informs the professional. I'm thrilled that, increasingly, business books have moved away from presenting ready-made organizational rules or simplistic personal success parables, and are increasingly complex studies that consider both the market forces and the intricacies of human experience that drive business and our day-to-day work, most often told within the framework of good storytelling and including implications for change and personal improvement. Today's business writing can offer a rich and enriching reading experience. But, it remains an obviously segregated genre.

I have come to believe that the personal is also the professional. Or, if that makes you uncomfortable, maybe that the personal informs the professional.

THE ELEPHANT AND THE MOUSE

So, what does that segregation within the canon of business literature mean for women in the workforce? It means it lacks a community of voices within which businesswomen can find communion. The need for gender parity available to businessmen and women is both obvious and nuanced. According to the Department of Professional Employees, in 2014, women made up just under half of the US workforce, but hold a slim majority of professional positions. That's the elephant: If business books are primarily written by men, no matter how gender-neutral, then how can they accurately represent the business lives of professional women? In addition, there is another underlying problem with the lack of women business writers that is less noticeable but no less destructive, and that is a problem of influence.

In “Men Explain Lolita to Me,” Solnit argues that the primary importance of gender equality in literature lies in our belief that art carries weight, even responsibility, because art has the capacity to change lives.

Photographs and essays and novels and the rest can change lives; they are dangerous. Art shapes the world. I know many people who found a book that determined what they would do with their life or saved their life.

So can we extrapolate out that business books (regardless of whether you believe them to be art or not) are influential, and thus, have a responsibility to represent workplace reality? Because that’s what the purpose of such books are. Business books are social science, they are self-help, they are philosophy, psychology, and theory. Business books aid in personal development, they redefine organizational theory, they are meant to be strategic and methodological game-changers. If business books really do influence as they are intended, if they really do change the way we think about business and the people who do the work that drives business, if we double-down on their importance, then why are we content to let one voice, that of white men, stand in for a more diverse and representative choir, and as a result, define what business is? To what extent do those of us who have any kind of platform allow this bias to keep happening? And at what point do we need to deconstruct the whole structure of the genre in order to eliminate passive acceptance of archaic practices?

So, if business books really do influence as they are intended…then why are we content to let one voice, that of white men, stand in for a more diverse and representative choir, and as a result, define what business is?

Why, if women in professional positions are the (albeit slim) majority, is business literature written by women still a minority, or a specialty? I'll return here to Solnit’s LitHub article because in it she cautions:

[T]here is a canonical body of literature in which women’s stories are taken away from them, in which all we get are men’s stories. And that these are sometimes not only books that don’t describe the world from a woman’s point of view, but inculcate denigration and degradation of women as cool things to do.

While I would defend contemporary business writing as being absent the overt degradation more common in the business literature in the ’70s and ’80s, I think it can be said that when it comes to business books written by women, there is still an unseen but sensed hand that waves away the importance of whether they exist or not. A shrug. A chuckle. Diffidence may be the word I'd now pick. Simply put, even in 2016, with the majority of business books, the author and the reader are presumed and expected to be male. Certainly, some authors and editors make a point of varying pronouns, but it’s uncommon for this choice to be anything but methodical, and even awkward. Ultimately, when men are allowed, even incidentally, to be experts on women's experience in the workplace, there is a certain thievery happening. I don't want anyone to own my story but me, or at the very least, I want someone like me to represent my point of view, even if it is on a topic that can be regarded as of multilateral interest.

Simply put, even in 2016, in the majority of business books, the author and the reader are presumed and expected to be male.

A TASK FOR FEMINISM?

So, changing the awards categories may seem like a token feminist move, more like the ’90s movement to reform words like women as womyn—i.e., short-lived semantics—than a true revolution. But I believe that categorization is one of the root causes barring women from entrance into the business genre. Categorization requires judgment, and if we judge business literature only by historical standards, then we miss the potential of new authors and ideas. All literature—or, rather, the seen and unseen critics that assign value—has had a tendency to laud male writers and ignore the female voice. This is the exact question that was at the heart of early feminism and remains an obstacle. If, as Solnit says, “So much of feminism has been women speaking up about hitherto unacknowledged experiences, and so much of antifeminism has been men telling them these things don’t happen,” then that was certainly true as women began using their voices to bang against the glass ceiling and remains true even in the presumption of progress.

And yet, we have the intrinsic push and pull that exists within feminism itself, which cannot be ignored when discussing business writing by women. It is evident in the backlash that books like Sheryl Sandberg's Lean In and Anne-Marie Slaughter's Unfinished Business received even as they were celebrated, and more particularly in the opposing opinions of these two powerhouse women. I won't get into the varied reactions that these two points of view received because that's an entirely different article, but it is important to understand just how difficult it is for there to be consensus about what feminism is, let alone how feminism behaves in business, from theory to practice, from writing to reading. Ultimately, such differing opinions work in women's favor in one particular way: the more voices, the greater the representation. We have lives as professional people; why weren't those lives being reflected in the literature? Yes, our experiences in a patriarchal system are unique to women, but we aren't limited to that subject matter. While there are certainly still workforce inequalities, how do we mainstream the experience of women CEOs, or salespeople, or entrepreneurs—especially if a new generation of business readers doesn’t ask questions of the system? What happens if we stop asking how the system is inherently stacked against women authors?

What happens if we stop asking how the system is inherently stacked against women authors?

SHINING A LIGHT

Restructuring our awards categories then leads to another rather entrenched difficulty, one that is continually being toiled over in regards to not only literature, but nearly all human production that gets dichotomized into male versus female, or even male and female. Isn't paying singular attention to women—creating special categories for women—just serving the same master of segregation? Shouldn't the goal be objectifying the subject matter so that there are no "women business writers" as I've been using here, but simply "business writers?" (Of course, then this article wouldn't exist, because there'd be no way to talk about the two divided and unequal groups.) This is the perspective of author Cheryl Strayed, who, in a Bookends column for the New York Times titled “Is This a Golden Age for Women Essayists?,” refutes that very construct because, she argues, “As long as we still have reason to wedge ‘women’ as a qualifier before ‘essayist,’ the age is not exactly golden.” Is the adjective “women” actually divisive rather than doing its work to shine the light on shadowy, uncelebrated understudies?

To some degree, it doesn't matter what the writer or publisher intends, but what the reader wants, or rather, what the reader presumes. I know that I have been guilty, even in my other In the Books articles defending women business writers, of apologizing to the assumed male reader for bothering them with a sort of feminist PSA. As late as 2014 I wrote: “Upon first glance at this post, you may feel compelled to ask: why are you singling out business books written by women authors about women in business, directed (at least to some degree) to a female audience?” I'm not saying that all men are still as entrenched in gender binaries as they were decades ago—the ones I know aren't, and yet, the ones I know are still often unaware of how the tradition has shaped their instinctive ability to assess.

I'll bet if you were to lay two books about leadership in front of a man, he's going to pick up the one written by a man. And what's wrong with this? As I admitted above, I always pick up the book written by a woman. I want to hear a woman's voice in my head when I explore my own internal system. But again, with business books, we—women, that is—have been assimilated into reading the man's voice, hearing the man's voice, and as such, at times internalizing the man's voice. As have men, really. The man’s point of view has become rote, barely distinguishable as being male, and is instead assumed to represent the universal. If readers don't have a new way of thinking about what makes good business literature, work that appeals to both genders regardless of authorial gender, how can we be certain that we are thinking about business in the most broad and widely accepting manner?

Stacey May Fowles, who addresses sexism in sports on her blog, writes this about the issue of responsibility and inclusion in an article titled “What The '93 World Series Taught Me About Sexism in Baseball”:

The reality is this: those who criticize your inability to foster a place for women within sports culture are on the side of right. You are failing. You are doing a bad job. You can say it’s hard, or time-consuming, or above and beyond what you’re willing to do, but that doesn’t negate that it’s your responsibility to rise to the challenge, and that it’s egregious if you are failing to do anything about it.

Replace “sports culture” with “business writing” and we have the sharp side of the knife, right? If we, as a company—writers, advocates, sellers—and if I as a manager, don't do the hard work, or rather, ask the hard questions, who will? I began to see that despite my steadfast belief in my own feminism, I was letting an assumption—business is men's business—define how we choose books to review and promote.

A RESOLUTION FOR EVOLUTION

Yes, I took Jane McGonigal's question personally. As General Manager of this women-owned book company, as a feminist and a feminist reader, why hadn't I asked the question: why weren’t there more women authors represented in our business book awards? Well, I'm asking it now: Why haven't we, as an editorial team, made a more deliberate effort to feature women business authors at the top of our awards? Why did I find it acceptable, shrug-able even, that there was only one book written by a woman on a shortlist of eight? And, was it ok for my gut response to be, “there are fewer female authors, so logically fewer winning books by women?” I didn't think so. And it falls on all of us to be aware and deliberate in how we question ourselves.

On behalf of Jane McGonigal and all other businesswomen and authors and readers, I decided to take up the mantel and set forth a few suggestions for our editorial staff for the new year:

- Challenge your belief that the male perspective is objective and the female perspective is subjective.

- Don’t assume a male readership while judging any book.

- Don’t assume a male readership of our reviews or recommendations.

- Reevaluate your awards criteria and editorial coverage to challenge the traditional and celebrate the multilateral.

- Question elitism in all business writing; our own included.

These are steps I hope all business readers will take in 2016. Make it a resolution of sorts: Let's talk about the presence, or lack thereof, of women's voices in business literature. Every one of us can contribute to the expansion and development of the business genre, and everyone one of us benefits from that growth. I'm committing 800-CEO-READ to take greater responsibility for our inadvertent participation in an out-of-date status quo, and to make a more deliberate effort to create a new conversation that treats books by women business authors equally—as opposed to as a specialty. But, even more so, I am reinvesting in my identity as a feminist reader, writer and leader, stubbornly advocating for the voices of women who will continue to enrich business literature.

Make it a resolution of sorts: Let's talk about the presence, or lack thereof, of women's voices in business literature. Every one of us can contribute to the expansion and development of the business genre, and everyone one of us benefits from that growth.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on this topic. Please email Sally (sally@800ceoread.com) with your feedback!