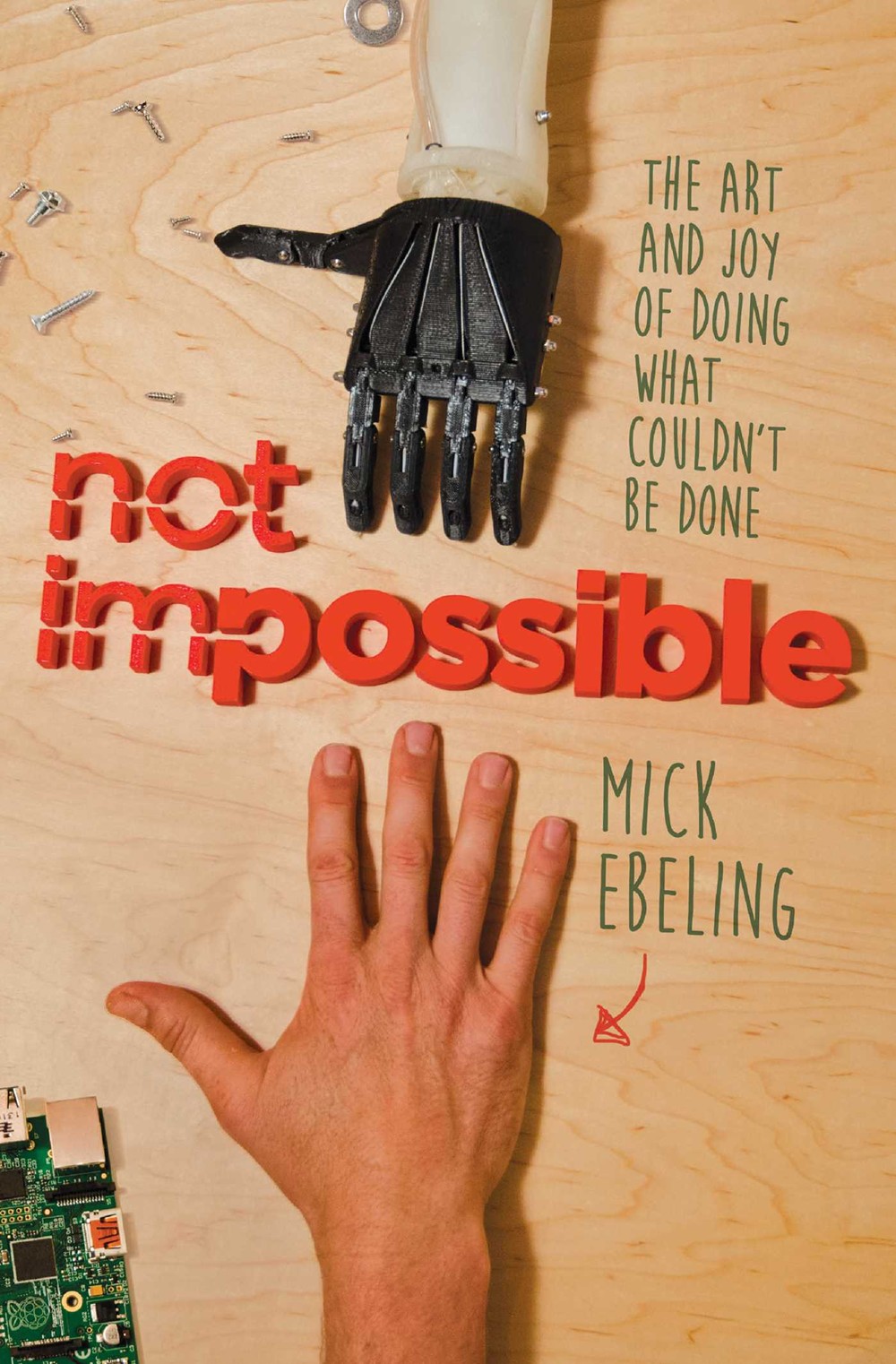

Not Impossible: The Art and Joy of Doing What Couldn't Be Done by Mick Ebeling

February 20, 2015

Doing the Not Impossible is often the result of first saying "Yes."

Over the past couple months, I’ve read both Amy Poehler’s Yes, Please and Tina Fey’s Bossypants (yup, I’m about four years late on that one despite being told on numerous occasions that Tina Fey is the one celebrity that I resemble), and in each, one common word kept popping up: “Yes.”

Amy Poehler wrote a book with the word “Yes” prominently in the title, and she explains why in this passage:

The “yes” comes from my improvisational days and the opportunity that comes with youth, and the “please” comes from the wisdom of knowing that agreeing to do something usually means you aren’t doing it alone.

Tina Fey writes: “Say yes and you'll figure it out afterwards.” And, also in regards to the practice of improv:

…the Rule of Agreement reminds you to “respect what your partner has created” and to at least start from an open-minded place. Start with a YES and see where that takes you.

So when I began reading Mick Ebeling’s Not Impossible: The Art and Joy of Doing What Couldn’t Be Done, newly released from Atria Books, it felt like kismet to see the title of his second chapter is: “Yes Is So Much More Fun.” In that chapter, Ebeling writes:

I did not set out to discover the power of Yes or the stunning energy that comes from surrendering yourself to the Not Impossible way of life. I did not set out to discover that that surrendering can do for your business, or what it can do for your soul, although in the years that followed, the power of Yes became all consuming, the guiding light that lit my days…and showed me where to plant my feet if I wanted to stand up straight.

Or, more succinctly, he advises:

“Say yes first, ask questions later. Commit, then figure it out.”

Echos of both Fey and Poehler. Generally speaking, my fears speak more loudly than my enthusiasms. I have many times in my life backed away from risk, and from its possible reward, because I found “No” to be a far more natural monosyllabic response to “Would you like to…?” than “Yes.” Yes creates uncertainty, and I, as opposed to Ebeling, like to plant my feet on solid ground. For me, reassurance comes from knowing just what it is I’m getting into and what the likely response is going to be.

Here’s Ebeling challenges to that kind of measured approach to life:

Right now, you’re probably facing some choices in your life, in your relationships, in your work, that are going to require you to make a decision. Go right, go left. Forge ahead, retreat. And you’re weighing the ups and downs, and maybe even doing what sensible people do and making a list—drawing a line down a piece of paper and putting the pros on one side and the cons on another.

But what if you didn’t?

What if you didn’t weigh the cons? What if you didn’t consider the what-ifs? What if you didn’t consider what would happen if you failed? What if you didn’t even allow for the possibility of failure?

Would that make you stupid? Or would that keep you focused and brave and alert and alive and aware?

What great questions. What a great last line. Poehler and Fey would probably agree that that aliveness is exactly why they too are so attracted to “yes,” or even that they credit their training in saying "yes" as foundational to their current successes.

When I was offered the position of General Manager here at 800-CEO-READ, I said yes. Actually, I think I said, “Yes!” And I said it in a way that I’d never said "yes" before. Now granted, you could look at my risk-taking as requiring very little risk, because I’ve worked for this company for 17 years, and I count the employees, and my bosses, as friends. How risky could it be? Regardless, the voice that said “Yes! I want to help this company and its employees do good work that we love, and I’ve got a vision for how we can do that” was more powerful than my usual voice that says, “Eh…I’m really happy here behind the scenes, doing what I always do.” Ever since then, ever since saying “Yes!” I’ve been thankful—and more “focused and brave and alert and alive and aware” than at any time in my career.

One of my favorite novels is A Room With a View, and in it, E.M. Forster is engaging with this same theme. A room with a view offers a person—the young Lucy Honeychurch in the novel—a glimpse at possibility, an opportunity for wonder, a life that embraces risk rather than rank. For Lucy, vacationing in Italy, it is venturing out into town with no guidebook and no chaperone. Through a series of events, she becomes involved with the Emersons, a father and son who do not respect the concerns of society, and the religious constraints that underlie it, with the same fervor as other characters in the book. Still, there is a push and a pull between living a life within the lines and living life regardless of lines. The father Emerson, hoping that his son will someday stop questioning and start engaging with life, with love, declares, “… by the side of the everlasting Why there is a Yes—a transitory Yes, if you like, but a Yes." The conviction behind my “yes” was that I believed I could help our company, and that in doing so, I could also help my family by forging a new career path that could bring us more financial security. That motivation compelled me to lean in, but perhaps it is my exposure to books like Fey's, Poehler's, Forster's, and now Ebeling's that have enabled me to get a glimpse of what is possible.

Ebeling, who would be the first to admit that he is naturally attracted to risk, and pursues it in his hobbies like surfing, is also motivated by the desire to help. The primary story at the start of Not Impossible is the development of an EyeWriter device for a young graffiti artist, Tempt, who has lost the ability to paint due to ALS. Ebeling has no experience with invention, nor any real experience with computer development. All he knows is that this man’s art inspired him to help the artist create that art once again. He dives in head first even if there are cautions ringing in his ears.

Let’s be clear. When I talk about overcoming that voice, I’m not talking about ignoring it or pretending it doesn’t exist. I am not fearless. I fear failure. And I fear failure a lot. But I teach this to my boys: When you are feeling afraid of something, or afraid you can’t do something, don’t deny that fear. Don’t just pretend it doesn’t exist. Allow it in. Say hello to it. Get to know it.

Tina Fey says something similar in Bossypants: “You can’t be that kid standing at the top of the waterslide, overthinking it. You have to go down the chute.” And it’s what E.M. Forster’s primary characters learn, to engage rather than question.

Ebeling succeeds in his efforts to enable Tempt to make art, and along the way, he brings together an unlikely group of supporters who fill in where Ebeling’s talents aren’t sufficient. Ebeling admits that he excels at storytelling, and “the power of story” can inspire change.

If you can show, over and over, on a daily basis, that people are doing the undoable, then you diffuse the power of impossible and its hold over people’s psyches. You unleash this army of people who are unstoppable, because they think, Oh, I don’t have to accept that—I can do this differently.

We can act as disrupters in our own lives, Ebeling says. But it’s true that we may not be able to do the impossible alone, and we have to let ourselves be touched by stories and then share those stories with others. After his success in spurring on the development of the EyeWriter, Ebeling learns of a young boy living in the Sudan who lost his arms in the war. Again, with no training but the help of others who are impassioned by the story, Ebeling heads to the Sudan where they create—and help other natives of the country learn to create—3-D printed prosthetics.

“What gets you out of bed?” Ebeling asks in Chapter 14, and its clear that the challenge to help others do the not impossible is what inspires him now, and offering all of us the courage to do the same is the message within his story. For some, the DIY or Maker movement is simply a natural state that compels them to create something out of nothing. For others, and I would suppose this is true for many of us who grow up and age in the era of fast technological advancement, making anything other than dinner is a foreign concept. But in whatever stage of creation you participate in, being part of ‘making’ a solution, rather than counting on someone else to do the impossible, makes everything in your life seem more possible.

Ebeling closes Not Impossible with a handful of success stories of other folks who are making a difference through the simple act of saying “yes” and then figuring out the ‘how,’ until the ‘why’ exposes itself. With both Fey and Poehler’s mid-life memoirs, it is clear that they are somewhat astonished, but yet not surprised to be where they are—creating art, empowering women, inspiring change, making everyone laugh--just from saying yes. And I suppose that’s where I'm lucky to find myself as well. I said “yes,” and I now have one helluva view.